|

METCHOSIN’S PROTECTED TREES You can download this in a PDF:TREE BROCHURE print ANY NATIVE TREE ONE METRE DBH AND ABOVE DBH = diameter at breast height (1.3m) Almost any native tree that is measured at one metre dbh will be at least 150 years of age. Large, old trees supply critical habitat for woodpeckers, bears, and many other species, and older trees have a crucial relationship with fungal root systems (mycorrhizae) that are critical to supporting forest health. GARRY OAK Poster child for our endangered Garry oak ecosystems and British Columbia’s only native oak tree, its calcium rich bark hosts abun- dant moss, lichen and insect communities. PACIFIC DOGWOOD BC’s provincial flower, its late spring floral display is breath-taking. The bright red clusters of berries are eaten by numerous birds including the blue-listed, band-tailed pigeon. ARBUTUS The only native, broadleaf evergreen tree in Canada, its white flowers are used by many pollinators and hummingbirds. Steller’s jays and others flock to its red or orange berries. ANY Arbutus tree 50 cm and above receives increased protection. MANZANITA This attractive bonsai-like shrub with red, peeling bark and ever- green leaves provides food for many bees, butterflies, humming- birds and other animals. CASCARA Over-harvested as a natural laxative, only the occasional young tree can still be found. Leaves turn a beautiful clear yellow in fall. Grouse and songbirds harvest the berries. WESTERN YEW Slow growing, it is the original source of taxol, a cancer-fighting drug. Many birds eat the bright red fruit (poisonous to humans) and the leaves supply food for black-tailed deer. SEASIDE JUNIPER Very rare, tree-sized juniper that has recently been recognised as a new species; appearance is similar to Rocky Mt. juniper. TREMBLING ASPEN Uncommon on Vancouver Island, although common in the BC Interior, there is a healthy population that shows a beautiful, yellow, fall colour at Witty’s Lagoon. OREGON ASH A red-listed, species-at-risk typically found in poorly drained, humus rich soil, in swamps, estuaries and seasonally flooded habitats. |

|

Please contact Metchosin District staff with any questions on the amended Tree Management Bylaw. 250-474-3167 or email www.metchosin.ca |

Monthly Archives: September 2013

Forage Fish in Metchosin

All articles and posts on the MetchosinCoastal website under the title Forage Fish may be found here:

In 2008 and in 2013, Ramona de Graaf, a biologist with the Public Education Program at the Bamfield Marine Station gave presentations on Forage Fish on our beaches and the need to Document their occurrence. In 2008 on the Saturday after the presentation, we rejoined for a walk and a session on the process involved in sampling for Forage Fish on Taylor Beach. Ramona is also the principal and founding marine scientist of Emerald Sea Research and Consulting.

- A group of Metchosinites go to Taylor Beach for a demonstration of beach sampling for forage fish eggs .

- A 30 metre line is laid out a metre below the strand line

- Ramona checking for sand lance egg locations

- mall trowel samples are taken of the pea gravel. Several samples make a collection to be examined.

- A set of sieves which can be home-made like these are used to sort the sand.

- The end sample in the .5mm sieve will be examined with a microscope.

- Small eggs of the forage fish roll on the sand surface.

- Wen-Ling Liao cleaning equipment after sampling.

Our thanks from the Blue-Green Spaces committee to Ramona and Wen-Ling for this informative session on the importance of monitoring and preserving forage fish habitat.

See also the post: Overhanging Vegetation, Invertebrates and Forage fish

See also Forage Fish of Metchosin and Beyond by Moralea Milne with an article by Briony Penn : The herring, the Chinook and the Orca…At the Brink. Moralea also documents a second training session by Ramona on Taylor Beach in March of 2009. Inclued is an article she wrote for the January Issue of The Metchosin Muse.

Throughout the Strait of Georgia, fish stocks have dramatically declined. Lingcod, rockfish and some Pacific salmon species are only some of the major commercial fish species in decline. Seabird populations throughout British Columbia and Washington State are also decreasing. As well, marine species such as the southern resident killer whale, dependent on salmon runs, have been listed as endangered. Many of these species depend on bait or ?forage? fishes as prey. Spawning habitat of forage fishes is located in nearshore marine environments, an environment heavily impacted by human development.

Documenting and protecting forage fish spawning habitats must be a priority for the Metchosin Coastline.

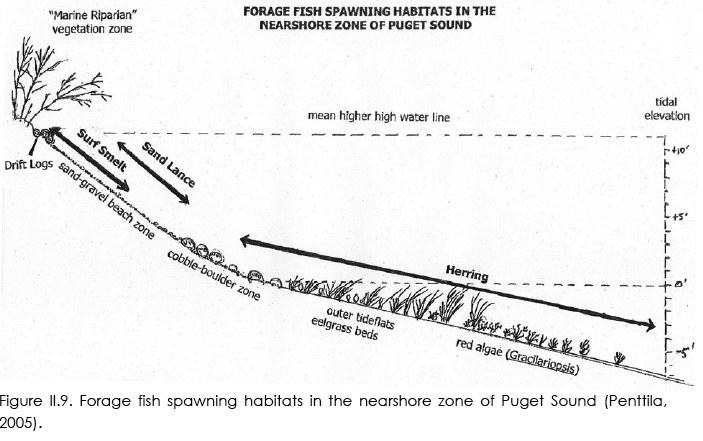

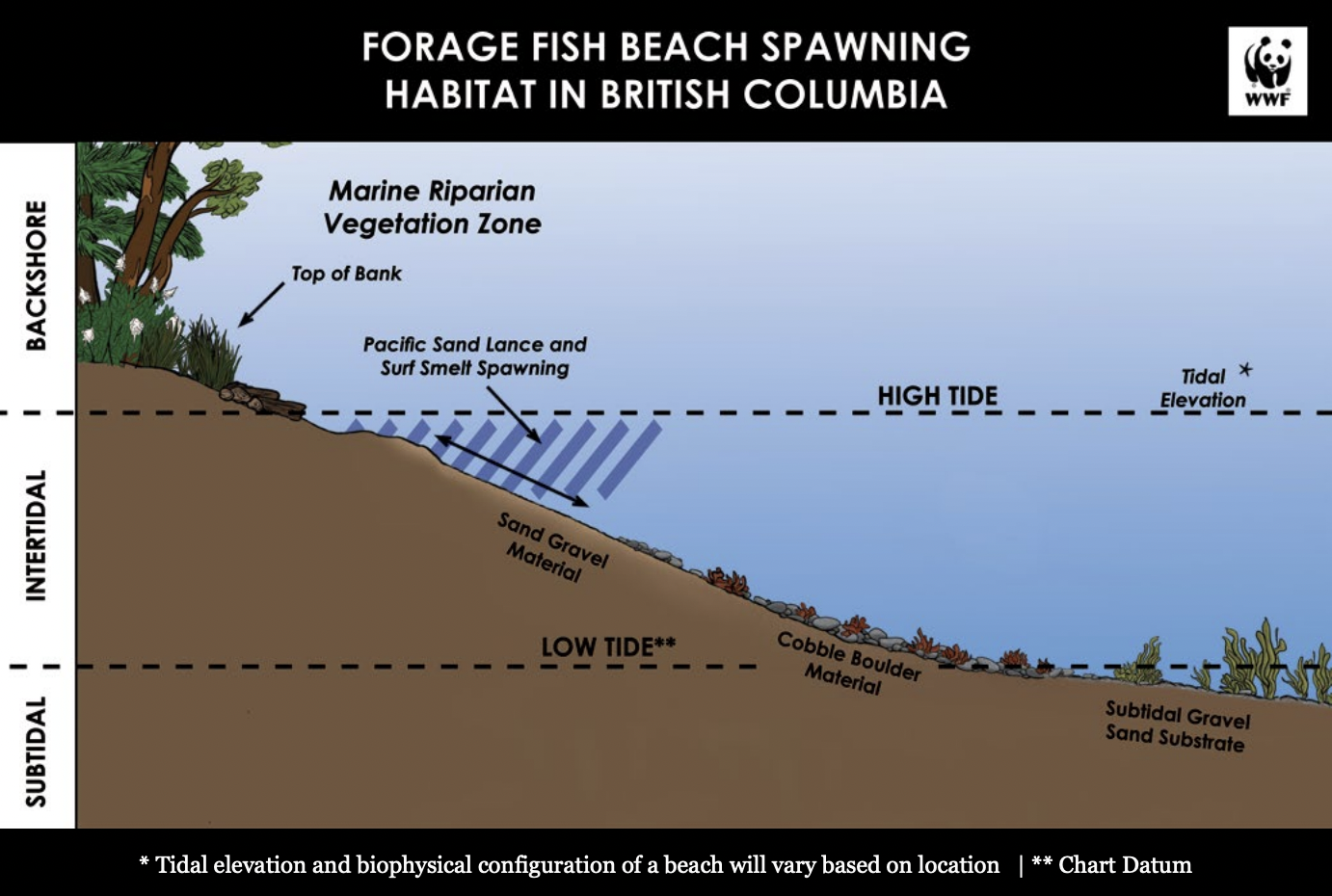

There is little information on the current extent and health of the spawning habitats of herring and no information on the spawning habitat of surf smelt and Pacific sand lance. Surf smelt and sand lance spawn in gravel/sand beach habitats in the upper one third of the intertidal zone (Figure 1). Current spawning habitats of surf smelt and sand lance have been documented throughout the US coasts of the Juan de Fuca Strait, San Juan Islands, and Puget Sound (Penttila 2000, 2001). In Canada, eelgrass beds are protected as critical fish habitat under Fisheries and Oceans Canada ?no-net? loss policy (Federal Fisheries Act). Protecting forage fish spawning and rearing habitats will have positive benefits by protecting a vital food source for numerous marine predators. Fisheries and Oceans Canada recognizes the need to obtain information on the habitat requirements of forage fishes in Coastal areas.

| Intertidal zone spawning locations. |

| WHAT ARE WE CONCERNED ABOUT WITH METCHOSIN’S BEACHES?

Diversion of sediment-bearing streams through culverts, and the backshore and intertidal placement of seawalls, outfall pipes and riprap armouring interrupt natural coastal processes (such as erosion) that supply terrestrially-borne gravel sediments to beaches crucial to spawning surf smelt and Pacific sand lance. Seawalls are physical barriers that block the seaward transport of eroding gravels from feeder bluffs. Impediment of the long-shore transport of sediments by groins, outflow pipes, piers, boat ramps and docks have all contributed to the sediment-starved state of some beach faces. In general, the placement of seawalls and riprap armouring in the backshore and in the intertidal continues the process of sediment deprivation due to the action of wave scouring. Wave scouring can result in the loss of fine sands and gravels (appropriate for spawning) and the dominance of coarser (larger) gravels and cobble beaches inappropriate for use as spawning gravels for both surf smelt and Pacific sand lance. Seawalls such as those onPreliminary Habitat Assessment for suitability of intertidally spawning forage fish species, Pacific sand lance (Ammodytes hexapterus) and surf smelt (Hypomesus pretiosus) Esquimalt Lagoon, Colwood , British Columbia and Tower Point are often placed in the backshore, supralittoral and high intertidal zones (the uppermost portion of the high tide range) which can result in the loss of spawning habitat area, a decrease in beach elevation, an increase in beach slope, interruption of the sediment-transport drift cell, and the loss of sediment retaining logs. Not only are these ?hard? approaches to storm protection negatively impacting forage fish populations, but they can fail to deliver the protection intended. Around the world and locally, there are growing incidences of seawalls and other armouring failing to protect land owners. Modern engineering approaches, or ?soft? approaches work with coastal processes to provide safety for human populations and industries as well as maintaining marine ecological functions. While this report will not address this topic in detail, several informative websites and consultants include http://www.greenshores.ca, http://www.coastalgeo.com, and http:// www.sanjuans.org.

Googlethe PDF : Preliminary Habitat Assessment for suitability of intertidally spawning forage fish species, Pacific sand lance (Ammodytes hexapterus) and surf smelt (Hypomesus pretiosus) Esquimalt Lagoon, Colwood , British Columbia |

Overhanging Vegetation, Invertebrates and Forage fish

page 6: Shorelines Connect – Linking The Land And The Sea

The Link between Salmon and Forest Ecosystem Productivity

In the past few years, Dr. Tom Reimchen of the University of Victoria and his students have established clear relationships between the health of Coastal forest ecosystems and the ocean through the food webs involving salmon. Below are links from the publications of Dr. Tom Reimchen to some of the research articles and papers they have published on this topic:

49. Reimchen, T. E. 2000a. Some ecological and evolutionary aspects of bear – salmon interactions in coastal British Columbia. Can. J. Zool. 78: 448-457. (.pdf version)

60. Hocking, M. D. & T. E. Reimchen. 2002. Salmon-derived nitrogen in terrestrial invertebrates from coniferous forests of the Pacific Northwest. BioMedCentral Ecology 2:4-14. ( http://www.biomedcentral.com/1472-6785/2/4/qc ) (.pdf version)

63. Reimchen, T. E. D. Mathewson, M. D. Hocking, J. Moran and D. Harris. 2003. Isotopic evidence for enrichment of salmon-derived nutrients in vegetation, soil and insects in riparian zones in coastal British Columbia. American Fisheries Society Symposium 34: 59-69. (.pdf version)

66. Mathewson, D., M.H. Hocking, and T. E. Reimchen . 2003. Nitrogen uptake in riparian plant communities across a sharp ecological boundary of salmon density. BioMedCentral Ecology 2003:4. (.pdf version)

70. Wilkinson, C. E., M. H. Hocking, T. E. Reimchen. 2005. Uptake of salmon-derived nitrogen by mosses and liverworts in Coastal British Columbia. Oikos 108: 85-98. (.pdf version)

76. Hocking, M.D and Reimchen T.E. 2006. Consumption and distribution of salmon (Oncorhynchus spp.) nutrients and energy by terrestrial flies Can. J. of Fish. and Aquatic Sciences 63: 2076-2086. (.pdf version)

87. Christie, K. S., M.D. Hocking, and T.E. Reimchen. 2008. Tracing salmon-derived nutrients in riparian foodwebs: isotopic evidence in a ground-foraging passerine. Can. J. Zool. 86: 1317-1323. (.pdf version).

98. Hocking, M.D., R. A. Ring and T. E. Reimchen. 2009. The ecology of terrestrial invertebrates on Pacific salmon carcasses. Ecol. Res. (.pdf version)

102. Darimont. C.T., Bryan, H., Carlson, S.M., Hocking, M.D., MacDuffee, M., Paquet, P.C., Price, M.H.H., Reimchen, T. E., Reynolds, J.D., & Wilmers, C.C. 2010. Salmon for terrestrial protected areas. Conservation Letters 3: 379-389. (.pdf version)

TR12. Reimchen, T. E. 2001. Salmon nutrients, nitrogen isotopes and coastal forests. Ecoforestry 16:13-17. (.pdf version)

TR15. Reimchen, T. E. 2004. Marine and terrestrial ecosystem linkages: the major role of salmon and bears to riparian communities. Botanical Electronic News. BEN#328. http://www.ou.edu/cas/botany-micro/ben/ben328.html

Crumia latifolia- wideleaf crumia moss

Crumia latifolia was one of the six special species recorded on the 2013 Bioblitz. The following was written by Kem Luther for the Bioblitz 2013 website

entered on iNaturalist at https://www.inaturalist.org/observations/33786772

” The Bioblitz moss group, (l. to r.) Wynne Miles, Olivia Lee, Steve Joya, and Kem Luther, look at Crumia latifolia. Photo by Garry Fletcher.

Garry Fletcher found this moss on a morning seashore foray along the shores of Parry Bay, at a seepage area above a rock beach. When he brought the moss back to the BioBlitz headquarters for identification, Steve Joya recognized it. The moss team made a detour in the afternoon to see Crumia in situ. “We only have a handful of collections from B.C.,” says Steve, “and these are mainly from islands in the Strait of Georgia area plus one from Limestone Island in Haida Gwaii…. I am not aware of any modern collections from Vancouver Island proper, so the Metchosin record was interesting.

Wilf Schofield, the late doyen of BC mosses, extracted this moss from a motley classification group and moved it to its own genus, naming it after the famous moss biologist, Howard Crum.”

Habitat and ID:

Crumia latifolia normally occurs on seepy shaded calcareous outcrops. The location on the Taylor bluffs is not normally considered to be calcareous.. The seeps originate from a deep glacial till layer.

- Vertical erosion bank at toe of bluffs

- Fresh water seeps at base of cliff

- Mosses growing in Fresh water seep.

- The mosses Pholia sp.and Crumia sp.

- Macrophoto of Crumia

- A clump containing Crumia latifolia

- Even in Juy, water seeps from the layers of glacial clay. Photos by Garry Fletcher

- The dark moss in the seeps is Crumia. This is on the cliff about 1 metre above the beach level

- Another moss growing in the same seeps is Brachythecium frigidum, Golden Short-Capsuled Moss.

| Kingdom | Plantae – plantes, Planta, Vegetal, plants | |

| Subkingdom: Viridaeplantae – green plants | ||

| Infrakingdom | Streptophyta – land plants | |

| Division | Bryophyta – hornworts, mosses, hépatiques, mousses, non-vascular land plants | |

| Subdivision | Bryophytina – mosses | |

| Class | Bryopsida | |

| Subclass | Dicranidae | |

| Order | Pottiales | |

| Family | Pottiaceae | |

| Genus | Crumia Schof. – crumia moss | |

| Species | Crumia latifolia (Kindb. in Mac.) Schof. – wideleaf crumia moss |