Witty’s Lagoon, B.C. Waterose et. al.

Judith R. Burke and: S. Ivanko, R. Luco, J. Walker, S. Wilmot

Index:

1. Introduction:

2. Geomorphology:

3. Biophysical:

4. Land Use and Governance:

5. Summary:

6. References:

Section 1. Introduction:

Inventories of terrain and geomorphology, ecology, and socio-economic aspects are required to appropriately guide human activities and developments. Topography, fauna, and flora inventories are also necessary to understand the underlying processes that control geographic and biotic distributions over space and time.

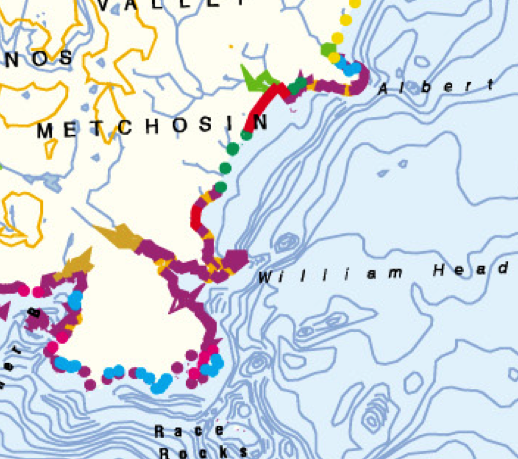

Witty’s Lagoon is located northwest of Victoria, on Vancouver Island, British Columbia.

Map

Land use issues, such as the preservation and enjoyment of the natural ecosystem and integration of anthropogenic uses, are prevalent governance issues for the future of the park and surrounding area. It is important to identify biological and geomorphic features of the area, as well as human impacts and socio-economic factors to develop sound coastal zone management plans.

1.1 Background:

A unique feature of Witty’s Lagoon Park is the wide range of habitats contained within the 51.4 hectares. From Metchosin Creek and the surrounding Douglas-fir forest, down to the lagoon and sea, this park supports plants and animals of many types. Witty’s Lagoon provides a wide range of family recreational actities. The ocean beach provides warm summer swimming, the forest area and lagoon offer year-round hiking, trails for horseback riding and diverse habitat for bird-watching (Weston, 1986).

Witty’s Lagoon was settled by a group of Coast Salish Indians called the Ka-Kyaaken. It is estimated that they arrived after the last glacier melted, about 10,000 years ago. Witty’s Lagoon Park contains traces of the village sites, two forts, and, numerous shell middens; ghosts of the lives gone past (Weston, 1986).

In 1851, after the signing of the Fort Victoria Treaties, Witty’s Lagoon was purchased by Captain James Cooper and was operated as the Bilston Farm by Thomas Blinkhorn. After a series of different owners, the Witty Family purchased the land in 1867 for $6000. Some of the early settlers on the Tower Point side of the Lagoon included the Hunt, Duke and Rosman families. More recently, the Capital Regional District (CRD) has owned and managed the park since 1969 (Weston, 1986).

Section 2. Geomorphology:

2.0 Ecosystem Analysis:

There were various types of ecosystems around Witty’s Lagoon. These can be broken down by their proximity to the type of water bodies which lie adjacent. The three main ecosystems are:

1. fresh water;

2. salt water;

3. and, transitional area.

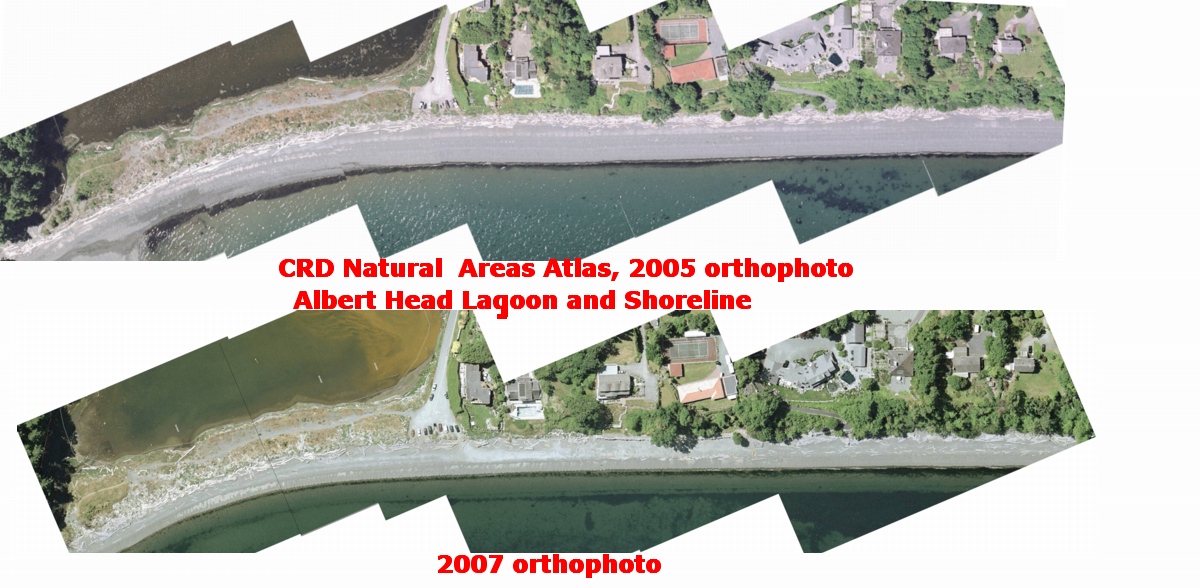

An overview of Witty’s Lagoon is illustrated in Figure 2.1.

Overview

Figure 2.1 Overview of Witty’s Lagoon

2.1 Fresh Water:

Waterfall The fresh water ecosystem includes the park area where the surface stream, Bilston Creek, flows through the forested trails and thunders over the towering waterfall. This waterfall is the physical boundary that separates the fresh water zone from the salt water zone at the high tide mark.

The park trail leads downward from the parking lot to the waterfall, at a rate of approximately one meter vertical for every three meters horizontal. The stream flows rapidly it approaches the waterfall at an estimated rate of 5 meters per second. The stream substrate is a unique feature known as volcanic pillow rock.

2.2 Transition:

Pillow Blocks The trail slope from the parking lot to the ocean beach is very complex. The trail consists of abrupt slopes by the water fall, and levels out as it descends to the ocean. Overall, the trail length is about 800 meters.

The stream bed consists of a volcanic rock substrate; the most common rock form is the unique pillow shape. This forms when a lava flow enters the water, and the outer layer cools, and fresh lava flows and forces the solidified rock to bulge outward. There is very little evidence of erosion of the pillow blocks.

The potholes in the stream were formed by the entrainment of rocks, such as grandiorites, which were scoured by materials carried in the high energy of the stream. Some of the potholes are 0.5 meteres in diameter.

Halfway between the waterfalls and the ocean, there is a micro-floodplain, with tall grasses and a small stream which is crossed by a small wooden footbridge.

2.3 Salt Water:

Beach This ecosystem is the most diverse. It has five sub-communities between the beach and the transitional that include:

1. Beach

2. Storm beach

3. Driftwood

4. Grassland

5. Spit

Each sub-community has distinguishing characteristics.

The cross section of the beach is illustrated in Figure 2.1.

Beach Cross Section

Figure 2.1 Cross Section of Beach

2.3.1 Beach Area:

The beach, below the high tide mark, consisted of a sand substrate that was deposited by longshore drift. It is a beach shaped by moderate energy forces because it faces south and is sheltered from the waves of high energy storms from the west. The sand substrate changed 10 cm below the low tide line, from sand to bands of cobbles. These range from 2.5 cm or less in diameter to unsorted rocks and pebbles greater than 10 cm diameter. The beach slope angled steeply into the ocean at 60%.

2.3.2 Storm Beach Area:

The storm beach, above the high tide mark, consisted of a loosely packed sand substrate and had a gentle 10% slope gradient. This area was 3 meters wide and the sand exceeded 25 cm depth.

2.3.3 Driftwood Area:

The driftwood area, above the high storm beach area, contained large logs which were deposited by the waves and storm energy. The driftwood formed a natural physical barrier that functioned as a natural retainer wall that anchored the organic soil layer above the beach. There was a sharp rise or step of 1 meter from the beach to the top of the soil layer where the logs were deposited. There were intermittent gaps in the wall of logs, where the sand and soils spilled from the grassland area above and down onto the beach. This transitional area of 1 meter wide included a mixture of logs, soil, sand, rocks, pebbles, and grass.

2.3.4 Grassland Area:

The flat grassland area, extended from above the driftwood area to the transitional forested zone. This area was characterised by many species of grasses and thick patches of the exotic scotch broom. This area of accumulated deposition is elevated above the beach zone and removed from the influence of the wave action; and hence, it was colonised by hardy floral salt tolerant species which formed the organic soil layer. The deeper sand would have a high salt content, from its past exposure to the waves and salt spray. The upper substrate was a mixture of unsorted rocks and sand. There were patches of exposed cobbles closer to the shoreline and pockets of sand deposits in the middle of the spit, presumably deposited by winds.

2.3.5 Spit Area:

The spit area is the landform that divides the offshore from the transitional high tide area. The sandy bar was 200-300 meters long by 50-75 meters wide. It was formed by wave refraction. Eddies scour the southwest corner and sediments are deposited on the opposite shore at similar rates. Wave action and outflow remove sediment from the beach point at the end of the bar and the bottleneck mouth to the lagoon. This equilibrium maintains the relative stability of the spit landform. The narrow mouth of the lagoon is kept open by the constant flow of water out of the estuary. The salt marsh, adjacent to the spit, is formed by stagnant water isolated from the main outflow energy from the lagoon.

Section 3. Biophysical:

3.0 Overview:

Witty’s lagoon is situated in a coastal bay where the formation of a beach barrier spit has created a lagoon. The biophysical and ecological features include a complex array of ecosystems; the four broad categories of the different types of communities are forest, salt marsh, spit, and, ocean beach. Each ecosystem has its own unique features and inhabitants.

The public access to the lagoon is from either a west or north parking lot. The beach trail down to the lagoon from the north parking lot is adjacent to Bilston Creek which thunders 50 meters down Sitting Lady Falls into the salt water lagoon. The southern trail travels down a steep slope through a rich coniferous forest, past an old overgrown farm homestead, through a salt marsh and out onto a floodplain where the lagoon begins. The trail continues along the flood plain and through grasslands out to a long narrow sandy barrier beach spit. The mudflats extend south of the spit while the salt marsh is on the north side of the beach spit.

The qualitative field survey techniques included: on-site descriptive observations; field notes; and, species identification of both plant and animal inhabitants and debris by informal transect and quadrat sampling techniques. Visual estimates of distance and per cent coverage were used. One limitation of the preliminary study was that the tide was high which excluded study of the sandy ocean substrate and the lower marsh substrate below the high tide zone. A second limitation of the field techniques used was that nocturnal species were excluded from the daytime observations.

3.1 Attributes of the Douglas Fir Forest and Flood Plain:

Douglas-fir (Pseudotsuga menziesii), sword fern (Polystichum munitum), and fungi occupy the forest from the canopy to the ground respectively. Douglas-fir is the dominant tree species with 60% canopy cover and an average tree diameter at breast height of 30 cm. The less dominant trees included some old growth and small regenerating Western red cedar (Thuja plicata). There are mature Arbutus (Arbutus menziesii) trees scattered along the edge of the forest adjacent to the lagoon. The roots of the trees adjacent to the lagoon curve down, out, and over the water. This suggests that the soil at the edge of the lagoon has slumped in towards the lagoon, forcing the trees to correct their growth upwards. There are at least four snags, large standing trees which are no longer living, which provide habitat to birds and animals. There are several habitat trees lying horizontally in the lagoon. The forest floor is populated by sword ferns with 40% ground coverage. Low on the moist forest floor there is a wide diversity of mosses and fungi. There were 5 separate species of fungi in a 10 metre random line transect along the forest trail. The fungi ranged from small orange caps, 5 cm tall and 3 cm cap diameter, to very large beige mushrooms, 15 cm tall and 30 cm cap diameter. Green moss thickly blankets the forest floor and tree trunks along the trail.

The trail continues down the slope, which is bordered by thick patches of blackberry shrubs (Rubus discolor) and oceanspray (Holodiscus discolor), to the old farmstead. The old farmstead contains several large apple trees and some big leaf maple trees (Acer macrophyllum). There are traces of the old farm fence still standing adjacent to the lagoon and salt marsh area.

The trail continues across the flood plain which supports shrubs, tall grasses, and a large stand of cottonwood trees (Populus balsamifera), and onto the beach barrier spit. The spit divides the ocean beach on the south from the salt marsh on the north.

Very few species of wildlife were observed in this zone; probably because most of the invertebrates normally found here were difficult to locate due to their small size. It is probable that a wide variety of invertebrates do exist in this area even though only six Banana slugs (Ariolimax columbianus) were observed on the trail to the spit. Terrestrial vertebrates were not observed; however, this terrain is suitable for burrowers and nocturnal hunters.

3.2 Attributes of the Salt Marsh:

The salt marsh has two distinct types of thick matted grasses. The thick grasses to the north end of the lagoon are brown in the standing water. The lush grasses to the south end of the lagoon are green, tall, and the 1 meter blades bend over forming a thick absorbent marsh bed. The tide was at the high level mark; however, it is possible that the salt marsh drains significantly at low tide level. There are several small islands, possibly of sand or rock, in the center of the lagoon covered with brown grasses. The north region of the lagoon is ringed by forest, brown marsh grasses, and log debris. The west region of the lagoon is flanked by a man-made sea wall and residential homes.

The north end of this sea wall is dominated by a 30 meter tall snag tree which stands out against the forested slope. The north area of the lagoon receives the highest volume of fresh water from Bilston creek. The south area of the lagoon receives the highest concentration of salt water from the ocean, and this is the area where the most of the salt water tolerant species of grasses are located. In addition, the marsh grasses must be tolerant to wet and dry periods during high and low tides. Large logs that are sparsely scattered across the deep grasses on the marsh side were probably deposited during severe winter storms with very high energy to move these logs over the spit to the protected leeward side. The edges of the marsh grasses are marked by narrow gentle slopes of fine clay like material into the lagoon.

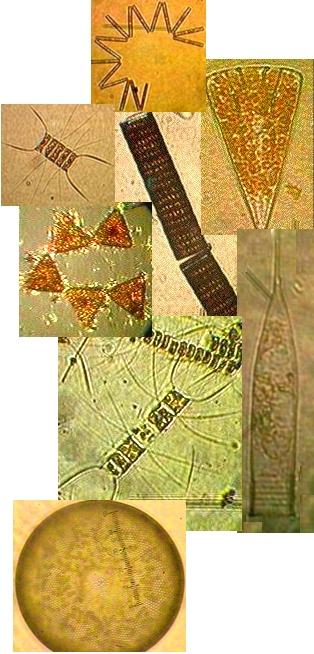

The brown water of the lagoon on the surface was still and calm. The swiftest flow of water is found at the south east end of the lagoon in the narrow channel, which is 20 meters across, where the ocean water flows in and the fresh water flows out. Here the water colour is a deep reddish brown, with a distinct line of coloration 1 to 2 meters below the water’s surface. The dark red colour may be attributable to tannins in the detritus of the fall leaves, or speculatively, may be due to an algae bloom event. An algae bloom event is caused by a population explosion of dinoflagellates. At this end point, the spit forms the bottle neck to the lagoon and provides protection from onshore winds and waves.

There was a wide variety of birds observed within the salt marsh. Table 1 lists the wildlife observed within the lagoon in order of decreasing dominance. Herring gulls (Larus argentatus), Glaucas-winged gulls (Larus glaucescens) and Mallard ducks (Anas platyrhynchos) were the dominant species within the lagoon. The ducks and gulls tended to flock together with respect to species and were observed feeding and swimming. A Cormorant was seen standing on a piece of driftwood floating on the lagoon while two Kingfishers were feeding nearby. Jays and Stellars Jay were observed flying over the lagoon and landing on one of the grassy islands. A Loon was also seen floating on the water. The wide variety of birds and bird types indicate an abundance of food, diversity of habitat, and the sheltered nature of the area.

Table 1. Species Observed in Salt Marsh

Table 1

3.3 Attributes of the Terrestrial Spit:

The beach barrier spit is accessed from the beach trail across the flood plain or from the stairs down from the west parking lot. The spit is 200 to 300 meters long, from west to east, and 50 to 75 meters wide, from north to south. The most notable feature on the terrestrial area of the spit is the dominant growth of scotch broom (Cytisus scoparius), covering 90% of the terrestrial area of the spit. This is an exotic species that was introduced to this area about the time the old farmstead was established. There is a variety of other shrubs, herbaceous plants, and thick grasses below the canopy of scotch broom. The picnic area near the west end of the spit is covered by short grasses. The spit rises slightly in the center; gentle slopes ease down on each side, towards the lagoon on the north side and towards the ocean beach on the south side. The peak altitude of the terrestrial portion of the spit is 5 to 7 meters above the high tide mark of the sandy beach.

The dominant faunal species in this zone was the Sand Flea. An almost infinite number of fleas and flea burrows were observed throughout the area. Walking quietly through the interior of the spit bar, two unidentified species of nesting birds were observed; a small nest and droppings found in the area are believed to house the birds. Red and black ants from the Order Hymenoptera were observed up to about 2 meters away from the anthill colony. Table 2 lists the species found in order from most plentiful number of organisms to of lesser numbers in population.

Table 2. Species Observed in Barrier Spit Bar

Table 2

3.4 Attributes of the Sandy Beach and Nearshore Marine Zone:

The narrow storm beach is subjected to high wave energy. The upper edge of the spit at the beach line is dominated by grasses in the humic top soil. There is an interesting band of 10 to15 cm diameter rounded cobble just below the humic line. One could speculate that this band of cobble is an anthropogenic enhancement to deter erosion of the top soil; however, the band of cobble lies below the humic stratification layer and is also found in the ocean sand below the high tide mark. This is additional evidence that this is a very high energy beach, commonly known as a storm beach.

The dominant vegetation at the top of the spray zone is salt tolerant and is likely spear grass or rye grass forming a band along the length of the spit. Adjacent to the grass band is the storm high tide line marked by extensive log debris along the entire length of the spit covering 40% of the sandy beach surface area at high tide.

Adjacent to this band of logs there is a band of ocean debris which covers 10% of the sandy beach surface. The ocean debris at this tide line is primarily seaweeds (algae) deposited by wave action onto the beach shore; however, there was anthropogenic debris including a plastic hair brush and a plastic coca cola classic bottle. The algae in the debris are indicators of the plant communities and associated substrates that exist nearby in the intertidal zone below the high tide water level.

The algae phyla included chlorophytes (greens), phaeophytes (browns), and rhodophytes (reds). There were delicate pieces of green algae; long pieces of brown bull kelp (Nereocystis lutkeana); and small multi-branched chunks of reds. An interesting specimen collected from the seaweed debris was a coraline red algae; bleached white, with small scale-like calciferous sections branching from a common base. The calciferous walls protect the algae from grazing predators.

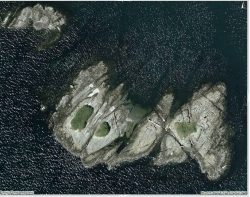

The seaweed debris is deposited upon a fine sandy beach which slopes gently southward down to the ocean. The beach matrix is 95 % fine grained sand with very few small rounded pebbles near the high tide line; however, there is a band of large rounded cobble in the intertidal zone which suggests deposition by high wave energy. The intertidal zone extends southward to a small rocky island 500 meters offshore from the beach. The island has 30% cover of grass vegetation and 50% cover of seagulls.

Sand fleas were the dominant species in the sandy beach zone. Table 3 lists all organisms observed in this area.

Table 3. Species Observed on the Sandy Beach and in Nearshore Marine Zone

Table 3

The majority of the fleas found were observed feeding on seaweed on the beach. A harbour seal pup carcass was found at the northeast tip of the beach. Hundreds of white maggots, about 0.5 cm in size, were feeding on the seal carcass. There was no evidence of internal organs remaining as the carcass was lying nearly flat on the beach. Part of the spine and skull were exposed and partially bleached indicating the seal pup had been dead for some time. The cause of death is unknown but may have been caused by a collision with a boat causing a fatal head injury, or many other possibilities. A sun bleached half jaw bone was also found near the seal carcass. The seven sharply pointed teeth and no grinding molars for vegetable mastication suggests that this was the jaw bone of a carnivore, possibly part of the seal’s jaw.

Three species of clam shell debris were scattered over the entire length of the beach, one of which was identified as the Native Littleneck clam (Protothaca stamiea). The sandy substrate of the nearshore beach zone would support a population of clams. One swimming scallop shell was found and would also have been deposited on the beach from the sandy substrate of the nearshore marine environment. Several small Acorn Barnacles(Balanus glandula), about 0.5 cm diameter, were found on pieces of driftwood washed up on shore. None of these barnacles were alive. A large Bull Kelp holdfast was encrusted with 5 very large (2.5 cm diameter) Acorn Barnacles, one of which was still alive. The barnacles are often present on a rocky substrate in the nearshore marine zone.

There were Polychaete worm tubes scattered over the entire beach. These tubes originated from a sandy substrate in the nearshore marine zone. Five small Red Rock Crab (Cancer productus) carapaces were identified ranging from 2.5 to 3 cm in length. A large leg from the same species of crab was also found. These crabs would have been consumed by marine shorebirds and deposited along the shore by wave action or birds.

Two species of seagull, the Herring gull (Larus argentatu) and Glaucus-winged gull (Larus glaucescens), along with about 17 seals were actively feeding, possibly on herring, in the nearshore marine zone about 50 meters from the beach. The seagulls were feeding in a tight circle about 3 meters in diameter, diving into the water and returning to the surface with tiny silver fish, possibly herring. The seals were exhibiting the same behaviour suggesting a large school offshore. It is unlikely that salmon would be present in Witty’s Lagoon because they would not be able to navigate the waterfall.

Section 4. Land Use:

4.0 Overview:

Historically, the park area was used by the Ka-Kyaakan band of the Northern Straits Salish people. Evidence of native culture in Witty’s Lagoon Park includes three shell middens and two fortified sites (CRD Internet). In 1850, the Hudson Bay Company purchased the land from Pedder Bay to Albert Head, and in 1851, the Witty’s Lagoon section was purchased privately; the native band continued to live on the beach for another century. The land was taken over by the Witty family in 1867 and used as farm land. Evidence of the European agricultural history includes apple trees, blackberries, a concrete irrigation weir and decaying fence posts. The authority in charge of the park, the Capital Regional District (CRD) has a mandate to protect and interpret archaeological resources; manage archaeological sites in cooperation with the Archaeology Branch of the Ministry of Small Business, Tourism and Culture, and maintain an inventory of historically significant sites (ibid.). This mandate is in response to the requirements of the Heritage Conservation Act, which was passed in 1994 (ibid.). The area comprising Witty’s Lagoon Regional Park was acquired by the CRD in 1969 and receives an average of 80,000 visitors per year (ibid.). The park is located south of Tower Point, on the southern end of Vancouver Island, within the Bilston Creek watershed. The CRD provides a parking lot, trails, nature house, and pit toilets; the park is used for a variety of purposes, including hiking, bird-watching, beachcombing, horse riding on designated trails, swimming, and picnicking. These activities are compatible with a multiple use model, and result in a high level of use, particularly during the summer months.

Land use within the Bilston Creek watershed is industrial, residential and agricultural. The headwaters of the creek are located along Humpback Road, and before the creek enters the park, it flows beside the highway, past a Lilydale Poultry Plant and through residential areas. The creek has marginal value for a cutthroat trout fishery, due in part to the high biological oxygen demand of the effluent from the Lilydale Poultry Plant (Bilston Watershed Habitat Protection Association, 1994).

The survey method used was both quantitative and qualitative: biota, geomorphology and land use were observed in the field; discussions were held with members of the Royal Roads University faculty; maps and air photos were used to aid interpretation of field observations, and coastal zone management issues were researched.

Coastal development near the park is limited to two residential areas that are 30 to 40 years old; one area is on the south side of Tower Point east of the lagoon, and the other area is southwest of the lagoon. The houses on Tower Point have a greater aesthetic impact on the park, as they line the lagoon outflow channel; the other houses are hidden from view by the forest. Most residents on Tower Point have left the shoreline in a relatively natural state; however, one residential lot has a cement brick retaining wall and highly cultivated lawn. There are two small private docks in the outflow channel; on one dock rested a canoe.

There are no artificial erosion devices in the park; Tower Point and the naturally formed spit protect the lagoon from the effects of storms.

Previous developments have impacted the park. Species, such as Scotch Broom and Himalayan Blackberries, are abundant in many areas of the park, and have irrevocably altered the ecosystems. The apple orchard affects a much smaller area, but along with the cement weir and fence posts, is still an important factor. The middens left by native people have likely changed the soil quality as the large quantities of shell material do not support plant life.

4.1 Description of Potential Values, Issues and Conflicts:

Witty’s Lagoon Regional Park is classified by the CRD as a nature appreciation park versus a recreation park, wilderness park reserve, or park corridor. The park features an active Nature Information Centre to aid in achieving this purpose. The value most strongly enforced by the CRD is therefore that of nature, rather than the historical and archaeological values. This contributes to potential land use conflict between park managers and first nations people who would like to have their history celebrated. There is also potential conflict between managers and those who use the area primarily as a recreation site. For example, there is no lifeguard at the beach, even though the beach is a popular swimming place. The CRD could also experience conflict with those who have little respect for nature, and disobey rules regarding littering and domestic animal control.

Development outside the park affects the water quality of Bilston Creek, and therefore has an impact on the management strategy of the CRD. Bilston Creek runs through residential areas where houses are dependent on septic tanks rather than municipal sewage. It also runs through agricultural areas and past Lilydale Poultry Plant; these factors all increase the nutrient loading of the water and change its properties within the park. Managers must decide how to cope with the enriched water – whether to leave it or attempt to restore it to natural levels. Agricultural run off and septic tanks will also affect the ground water, which drains into the park. Any pesticides applied to crops will be able to enter the park, and nutrient rich water entering the lagoon will promote eutrophication.

The CRD is responsible for allocating funds to the 19 regional parks; therefore, difficulties may arise between individual municipalities who feel that the parks within their boundaries deserve a greater portion of funds. The CRD must maintain trails and facilities with an efficient and effective distribution of funds; this distribution is not simple to define. Trail widening is evident, and is considered to be a problem in need of CRD-led remediation. Conflict may well arise when this issue is tabled by the CRD.

The final potential conflict is between park users and local residences. This is a common problem when residential areas border parks, especially those with high recreational value such as the beach at Witty’s Lagoon. The establishment of the park in 1969 occurred after the construction of nearby residences. Residents may be disturbed by park visitors who are loud late at night, or who behave inappropriately. Park visitors, on the other hand, may not be impressed by the intrusion of houses in a natural area.

An upcoming issue is that of the proposed development at the Construction Aggregate gravel pits. Over the next 20 years, an estimated 5000 houses are scheduled to be built in the area (Robert Gale, personal communication). This will no doubt increase park usage and test its carrying capacity. This could have a negative effect on the biodiversity of the park and the health of the ecosystems.

4.2 Governance:

Witty’s Lagoon Regional Park covers an area of 56 hectares and is administered by the CRD as one of 19 regional parks, covering some 9000 hectares. It consists of a range of biophysical units, making governance a complex issue and long term planning crucial. The CRD was organized in 1966, and in 1993 was expanded to include 12 municipalities and 4 electoral (unincorporated) areas. The CRD is governed by a Board of Directors who represent the various member organizations and whose meetings are open to the public. The public has four ways of bringing an issue to the board:

1. Getting an item on the board agenda which involves presenting the item to one of the representatives to the Board from your local government;

2. Making a presentation to a CRD committee;

3. Speaking directly to the CRD board of directors; and,

4. CRD board committees and commissions.

As such, the public can be involved in the planning of the park and concerns can be heard. The CRD is responsible for trail maintenance and development, maintenance of other facilities, staffing the Nature Information Centre, and providing proper signs. Any concerns regarding issues such as the need for a lifeguard, or the effects of future housing developments should be addressed the CRD.

The CRD has realized the importance of the regional parks system, both ecologically and in terms of the human value. The Official Regional Parks Plan (ORPP) guides the actions of the CRD, and is currently being updated. The public has an opportunity to participate in updating the plan by participating in a Public Advisory Group (PAG) The goal of the PAG is “to bring together a diverse group of people from throughout the CRD, and who represent a broad range of interests, to provide advice to the CRD Parks Committee about the future of CRD Parks.”

The District of Metchosin plays a greater role in the governance of Witty’s Lagoon than other CRD members, since it borders the south end of the park, and Bilston Creek and many of its tributaries run through Metchosin before entering the park. Since this is the area in which Bilston Creek becomes contaminated, Metchosin must take responsibility for the condition of the creek entering the park. Bilston Creek runs through residential areas in Metchosin where houses are dependent on septic tanks rather than municipal sewage, as well as agricultural areas, and the Lilydale Poultry Plant.

Section 5. Summary:

Witty’s Lagoon Regional Park and the surrounding areas are important multi-use landscapes in the Capital Regional District. The park maintains an ecologically important green space and provides educational and recreational uses to the public.

Witty’s Lagoon Regional Park consists of several biophysical units, which enhances its ecological interest and value, in terms of maintaining biodiversity of the region. The upper reaches of the park are primarily Douglas fir, with a sword fern understory. The only fauna found in this area were banana slugs, but evidence of other wildlife included habitat trees. Proceeding towards the lagoon, one comes across an area which has been cleared and is impacted by human development. This is the site of the farmstead which was active in the late 19th century and early 20th century. Visible impacts include the introduction of exotic species such as Scotch Broom, Himalayan Blackberries and apple trees. The spit is also covered with Scotch Broom, to such a extent that eradication is next to impossible. The spit has been formed by deposition in the form of longshore drift. The lagoon area is a refuge for water fowl, including ducks, cormorants and gulls. This area is becoming more significant, especially for migratory birds, as other habitat is destroyed by urban development.

One of the main attractions of the park is Sitting Lady Falls which is near the end of Bilston Creek. The three main areas of the lagoon are the freshwater, transition and salt water zones. Each is shaped by different geomorphological processes: the waterfall cascades down a bed of pillow basalt, which forms three sides of the lagoon. The transition zone lies between the landward side of the spit and the waterfall. The main forces in this area are the river current and tidal action. The salt water zone lies between the ocean front and the transition zone. It is shaped by wave action and ocean currents. The beach will continue to be formed by wave action and wind.

Agricultural uses continue to input nutrients into Bilston Creek; the discoloration of the lagoon could be due to an algal bloom, resulting from the nutrient loading. Testing of the lagoon for the cause of the discoloration is recommended, so that the public can be made aware of the cause and any associated risks.

Socio-economic considerations are unlikely to undergo a significant shift, as land use issues have been fairly static for the past 20 years. However, proposed developments in the surrounding areas will impact the park if they proceed. The CRD has recognized the importance of public input to decision making and the Public Advisory Group has been established as a forum for residents to voice any concerns.

In addition, the public could be more informed regarding the historical and archeological significance of Witty’s Lagoon.

Section 6. References:

The Naturalist’s Guide to the Victoria Region. 1986. Cd. Jim Weston’s & David Stirline. Victoria Natural History Society.

Bilston Watershed Habitat Protection Association. A summary of field investigations, Victoria, BC, November, 1994.

CRD Internet Site: Information about CRD Areas URL: http://www.crd.bc.ca

Capital Regional District Parks, Witty’s Laggon Region Park Management Plan. Nov. 1994. Victoria, BC.

Waterose et. al.

Judith R. Burke

and: S. Ivanko, R. Luco, J. Walker, S. Wilmot

11.

11.

Often in the spring when the sunlight levels are adequate, the nutrient laden water from winter run-off may support a non-poisonous red tide. A deep reddish bloom caused by the organism Mesodinium rubrum will cover parts of the bay. This is a unique marine photosynthetic ciliate which can fix energy because it has a cryptophyte endosymbiontic red algae inside it. A good example of a mutualistic relationship occurring on a massive scale within the bay.

Often in the spring when the sunlight levels are adequate, the nutrient laden water from winter run-off may support a non-poisonous red tide. A deep reddish bloom caused by the organism Mesodinium rubrum will cover parts of the bay. This is a unique marine photosynthetic ciliate which can fix energy because it has a cryptophyte endosymbiontic red algae inside it. A good example of a mutualistic relationship occurring on a massive scale within the bay.