It is clear that the province must not abdicate coastal protection to other levels of government. Because the province has not yet legislated a strategy and overall plan for our coast:

•The federal National Energy Board’s hearings on the Northern Gateway

Project – the most important coastal management issue to face BC in

decades – will be decided by a three person panel, none of whom are

British Columbians. Unfortunately, BC failed to plan beforehand about oil

ports and other infrastructure decisions;

• When industrial interests objected to funding arrangements, Ottawa’s

process for developing a north coast ocean management plan faltered.

That process is now likely to ignore major issues such as oil terminals.

Although the province and First Nations are now working to create Coastal

Management Area Plans, they are doing so without a clear statutory

mandate;

• It took the Cohen Commission to remind us that the future of salmon

rests as much upon actions of BC as on Canada. Salmon are affected by

stormwater, riparian development and numerous activities under provincial

jurisdiction. Yet there has not been a co-ordinated federal/provincial

strategy to protect salmon and our coast; and

• Most coastal resources are common property with ill-defined access rights.

This has caused overuse, neglect and degradation of essential ecosystems.

This problem has not been addressed.

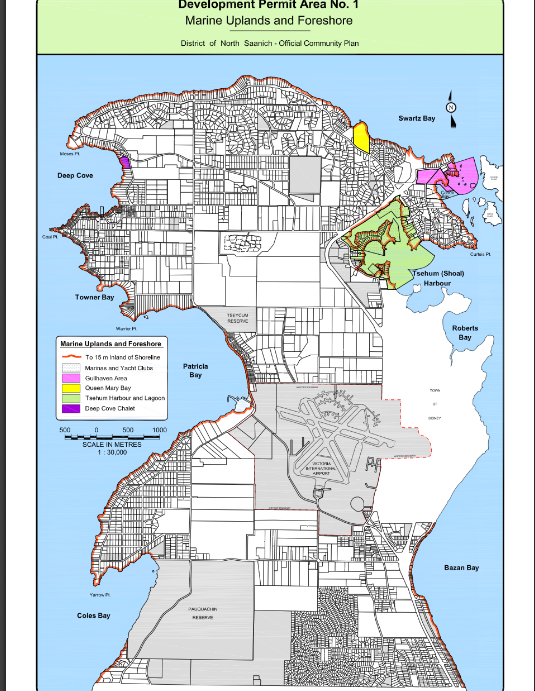

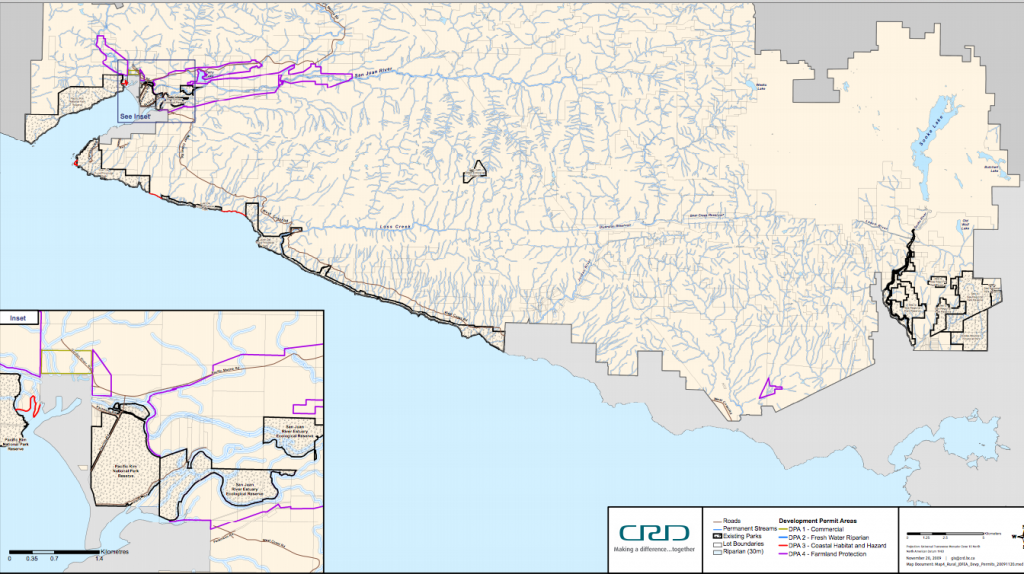

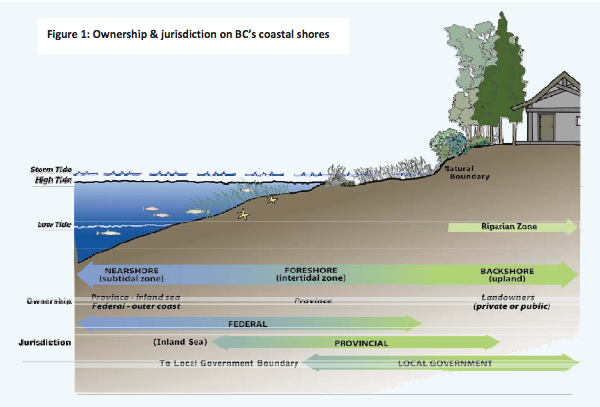

Coastal Jurisdiction and Ownership

Management of coastal and marine resources is an area of complex, shared

jurisdiction between all orders of government, including First Nations and

local governments. For example, Ottawa has jurisdiction over fisheries

regulation and navigation. Local governments have zoning and other powers

over local shorelines and some coastal waters.

Meanwhile, the province has broad regulatory jurisdiction over numerous

activities in the coastal zone. In addition, it has jurisdiction and ownership

over the foreshore seaward of the high tide mark and all coastal or “inland”

waters within the “jaws of the land,” including the seabed. The seabed of

the Strait of Juan de Fuca, the Strait of Georgia, Johnstone Strait and Queen

Charlotte Strait are the property of British Columbia.

As a consequence, the coastal ecosystem is regulated by a plethora of

agencies from numerous governments. This thwarts effective planning

and management – especially because of the absence of effective legislative

mechanisms to coordinate the actions of multiple agencies.

Thus, it is not surprising that management of the coastal zone has been

more problematic than terrestrial resource management. The province

needs to address this. It needs to create a legislative framework to assert

jurisdiction and ownership of coastal resources – and to coordinate with other

governments

page 79: