Monthly Archives: May 2013

Preparing for Climate Change: DPAs

Hardening of the Shorelines: Principles

The following is from :

Shorelines Modification , by the State of Washington Dept of Ecology

(ii) Principles. Shorelines are by nature unstable, although in varying degrees. Erosion and accretion are natural processes that provide ecological functions and thereby contribute to sustaining the natural resource and ecology of the shoreline. Human use of the shoreline has typically led to hardening of the shoreline for various reasons including reduction of erosion or providing useful space at the shore or providing access to docks and piers. The impacts of hardening any one property may be minimal but cumulatively the impact of this shoreline modification is significant.

Shoreline hardening typically results in adverse impacts to shoreline ecological functions such as:

- Beach starvation. Sediment supply to nearby beaches is cut off, leading to “starvation” of the beaches for the gravel, sand, and other fine-grained materials that typically constitute a beach.

- Habitat degradation. Vegetation that shades the upper beach or bank is eliminated, thus degrading the value of the shoreline for many ecological functions, including spawning habitat for salmonids and forage fish.

- Sediment impoundment. As a result of shoreline hardening, the sources of sediment on beaches (eroding “feeder” bluffs) are progressively lost and longshore transport is diminished. This leads to lowering of down-drift beaches, the narrowing of the high tide beach, and the coarsening of beach sediment. As beaches become more coarse, less prey for juvenile fish is produced. Sediment starvation may lead to accelerated erosion in down-drift areas.

- Exacerbation of erosion. The hard face of shoreline armoring, particularly concrete bulkheads, reflects wave energy back onto the beach, exacerbating erosion.

- Ground water impacts. Erosion control structures often raise the water table on the landward side, which leads to higher pore pressures in the beach itself. In some cases, this may lead to accelerated erosion of sand-sized material from the beach.

- Hydraulic impacts. Shoreline armoring generally increases the reflectivity of the shoreline and redirects wave energy back onto the beach. This leads to scouring and lowering of the beach, to coarsening of the beach, and to ultimate failure of the structure.

- Loss of shoreline vegetation. Vegetation provides important “softer” erosion control functions. Vegetation is also critical in maintaining ecological functions.

- Loss of large woody debris. Changed hydraulic regimes and the loss of the high tide beach, along with the prevention of natural erosion of vegetated shorelines, lead to the loss of beached organic material. This material can increase biological diversity, can serve as a stabilizing influence on natural shorelines, and is habitat for many aquatic-based organisms, which are, in turn, important prey for larger organisms.

- Restriction of channel movement and creation of side channels. Hardened shorelines along rivers slow the movement of channels, which, in turn, prevents the input of larger woody debris, gravels for spawning, and the creation of side channels important for juvenile salmon rearing, and can result in increased floods and scour.

Additionally, hard structures, especially vertical walls, often create conditions that lead to failure of the structure. In time, the substrate of the beach coarsens and scours down to bedrock or a hard clay. The footings of bulkheads are exposed, leading to undermining and failure. This process is exacerbated when the original cause of the erosion and “need” for the bulkhead was from upland water drainage problems. Failed bulkheads and walls adversely impact beach aesthetics, may be a safety or navigational hazard, and may adversely impact shoreline ecological functions.

“Hard” structural stabilization measures refer to those with solid, hard surfaces, such as concrete bulkheads, while “soft” structural measures rely on less rigid materials, such as biotechnical vegetation measures or beach enhancement. There is a range of measures varying from soft to hard that include:

- Vegetation enhancement;

- Upland drainage control;

- Biotechnical measures;

- Beach enhancement;

- Anchor trees;

- Gravel placement;

- Rock revetments;

- Gabions;

- Concrete groins;

- Retaining walls and bluff walls;

- Bulkheads; and

- Seawalls.

Generally, the harder the construction measure, the greater the impact on shoreline processes, including sediment transport, geomorphology, and biological functions.

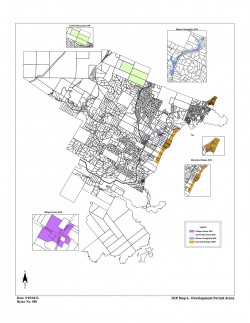

District of Metchosin Official Community Plan Section on Shoreline Slopes Development Permit Areas

From the Official Community Plan : Available at this link

2.16 SHORELAND SLOPES DEVELOPMENT PERMIT AREAS:

The Municipal Act

provides that a community plan may designate development areas to be protected from hazardous conditions. The Municipal Act further provides that in such areas land shall not be altered in any way or subdivided and structures not be built or added to until a Development Permit has been issued. Council has established the following designation, special conditions, and guidelines.

2.16.1 Designation: (Bylaw 418, 2004)

The 1993 Hazard Land Management Plan has identified areas of the Metchosin shoreland slopes as having erosion, land sloughing and drainage problems.

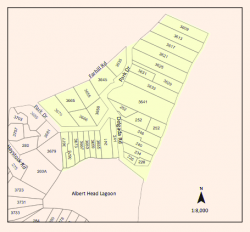

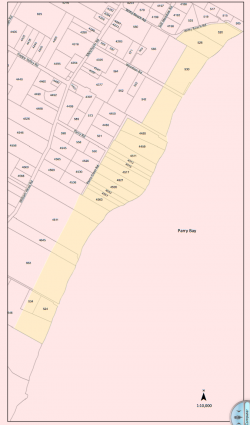

The Shoreland Slopes areas are shown on Map 6 Shoreline Slopes DPA, and are hereby designated as areas for the protection of development from hazardous conditions pursuant to Section 919.1(1)(b) of the Local Government Act.

The Plan has identified three Shoreland Slope classification zones, based on the degree of slope instability and surface erosion potential. Slopes classified as zone 2 and 3 are slopes with the greatest potential for sloughing, slumping and debris flows and have been included in the Development Permit Area.

2.16.2 Special Conditions:

The major concern is that lands, particularly in the Park Drive – Farhill Road area, have experienced a dramatic rise in ground water levels due to adjacent developments during the last two decades. Other areas of the Shoreland slopes have experienced significant slope erosion in the past. There is a community desire to mitigate any further development related impacts on the marine shorelands.

2.16.3 Policies Development Permits issued shall be in accordance with the following:

(1) The construction or alteration of buildings on existing lots shall be permitted subject to the Building Permit process when Council is satisfied that the Development Permit Guidelines (Section 2.14.4) have been met, and, when required, Council is satisfied with the Engineer’s Report (Section 2.14.5).

(2)Where a Development Permit is applied for in conjunction with an application for subdivision approval, rezoning, or both, the Development Permit shall be conditional on the successful completion of those other permits and shall lapse if the subdivision or rezoning is not approved.

2.16.4 Guidelines:

(1) All applications for new development in the Development Permit Areas shall be required to have an Engineer’s Report (described below).

(2) Removal of vegetation shall be minimized.

(3) House construction, regrading, and excavation of till (including for road building) is not permitted within 60 metres of the edge of the slope except where geotechnical engineering and resource management studies indicate that a lesser setback is acceptable.

page 31

‐

2.16.5 Engineer’s Report:

Before a development permit is issued, the applicant shall be required to furnish a report at his\her expense from a registered professional engineer with geotechnical experience which will certify that the proposed development will produce no adverse impacts on the shoreland slopes and will not place buildings or structures in danger of slope slippage.

The Engineer’s Report shall demonstrate that consideration has been given to the following:

(1)(a) siting and setbacks of development structures, roads, and services,

(b) minimizing paving and impervious materials, and,

(c) implementing infiltration techniques so as to limit runoff;

(2) designing runoff detention ponds, drainage works, or

sediment traps or basins to reduce the flow of runoff and silt during land clearing and construction.

(3) development near shoreland slopes must address the impact of surface water on slope stability, vegetation and soils, and make recommendations to remedy that already damaged; and

(4) removal of trees (with a valid tree-cutting permit) or other vegetation should be allowed only where necessary and where alternate vegetation and/or erosion control measures are established. If possible, stumps should be left in place to provide some soil stabilizing influence until alternative vegetation is established. Plans delineating extent of vegetation/tree removal (location, species and diameter of trees) and location of proposed construction, ex cavation and/or blasting, may be required.

The DISTRICT, at its discretion, may also submit the Engineer’s Report to review by a second Engineer at the applicant’s expense, and/or directly to the Ministry of Environment for their comments.

2.16.6 Municipal Response,

The DISTRICT should:

(1) evaluate the feasibility of purchasing environmentally sensitive shorelands for use as park, forest reserve, or greenbelt;

(2) initiate programs to monitor both surface and ground water to establish patterns of change;

(3)work with proximate agencies to establish erosion and land sloughing control measures.

Acanthodoris nanaimoensis–the wine-plumed spiny dorid nudibranch

On May 26 2013, Gretchen Markle reported on a nudibrach

” Today we found two specimens of the grey phase Acanthodoris nanaimoensis (unmistakable with its maroon-tipped rhinopores and gills) on the beach at Chris Pratt’s.” (see location image below.)

The range of this species is Baranof Island, Alaska to Santa Barbara, CA; less common in southern portion of range.

Click on this image from Google Earth 3D for the location.

Henricia pumila–dwarf mottled Henricia

Gretchen Markle reported a new seastar Henricia pumila for the April 27 Metchosin Bioblitz on the Laird’s beach , south of Taylor Road and north off Weir’s beach (see Google image below). Henricia pumila is an uncommon seastar, having only been officially described in 2010. Phil Lambert confirmed the identification.

See http://www.mapress.com/

- Henricia pumila ,Eernisse et al., 2010 Dwarf mottled henricia

- Photos of H.pumila by Gretchen Markel

- Henricia pumila on Chris Pratt’s Beach

Phylum Echinodermata

Class Asteroidea

Order Spinulosida

Suborder Leptognathina

Family Echinasteridae

Genus Henricia

Species pumila, Eernisse et al., 2010

Common name: Dwarf mottled henricia.

Anything for a View?

Living on a steep coastal bluff with million dollar views may be a dream of many, but with it comes a few responsibilities. The references on development along coastal areas provides many examples of how development has to be done responsibly. One aspect of concern is vegetation removal and tree cutting and topping on cliffs in order to provide better views to the landowner. In Metchosin, two areas, the Albert Head Cliffs and the Taylor Beach Cliffs provide many examples of this.

In April of 2013 the sound of a chainsaw on the Taylor cliffs led to the discovery of many alder trees on the almost vertical slope that had been topped and even a few arbutus trees had been cut down.

These trees were about 25 years old as can be seen by the tree rings on chunks of trees that had rolled down to the beach.

These trees were about 25 years old as can be seen by the tree rings on chunks of trees that had rolled down to the beach.

It might be pointed out that these trees are from the area of Metchosin’s Coastline included in the development permit zone.

This reference from the Center for Ocean Solutions points out he problems of interferring with natural processes on an seaside cliff given the threats of climate change and sea level rise.

A good example taken from “Mail Online” of what slope failure looked like on Whidbey Island.

Evasterias troscheli–mottled star

These photos taken by Garry Fletcher on the rocky intertidal at the base of Taylor Bluffs on Parry Bay shows an unusual green phase of the Evasterias troscheli

- The sea star Evasterias eating Mopalia chitons.

- A green version of the mottled star, Evasterias sp.

| Kingdom: Animalia |

| Phylum: Echinodermata |

| Subphylum: Eleutherozoa |

| Superclass: Asterozoa |

| Class: Asteroidea |

| Order: Forcipulatida |

| Family: Asteriidae |

| Genus: Evasterias |

| Species: E. troscheli |

| Binomial name: Evasterias troscheli, (Stimpson, 1862) |

Metchosin Bioblitz 2013: North end of Sector 7, Taylor Beach

Metchosin BioBlitz Observations by Garry Fletcher and Sandra______on April 27, 2013 on the floodplane and estuary of Gooch Creek, on the 4645 William Head Road Property.

- Vertical erosion bank at toe of bluffs

- Fresh water seeps at base of cliff

- Team of Bryologists and Kem Luther examining habitat of Crumia sp.

- Mosses growing in Fresh water seep.

- The mosses Pholia sp.and Crumia sp.

- Mute swans– feed off Taylor beach , nest in Sherwood pond.