By Garry Fletcher, Metchosin, British Columbia

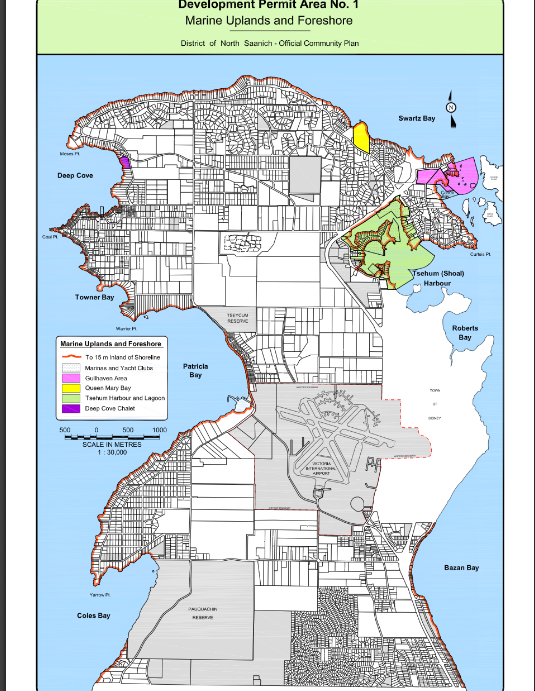

The yellow dots show the margin of the Gooch Creek Estuary. The populations of native Phragmites are shown in red. Location: 48deg,22′,11.01″N—123deg 31’52.19″ W.

Introduced species are no doubt one of the most serious challenges for us in the effort to preserve ecological integrity*. Occasionally however we can mete out a death sentence to an innocent which can have serious consequences. This post is about one such occurrence with the native marsh/estuary grass Phragmites australis (Cav.) Trin. ex Steud. subsp. americanus

When we first bought our property on William Head Road, I was intrigued with the variety of ecosystems that could fit into one small 4 hectare piece of land. One such ecosystem was the seasonally flooded salt marsh at the foot of the property. In that marsh were two populations of a very tall (2-3 metre) marsh reed grass.

In the mid-1980s, I asked one of our members of * MEASC, Robert Prescott-Allen to identify the species for me and he came up with the genus name Phragmites. He indicated that it used to be more common in our coastal estuaries, but it had been destroyed in the early years with cattle trampling and grazing. Now it only occurs in limited populations in BC and in some populations along the Oregon Coast.

When I made the website MetchosinCoastal , I included a profile on the marsh with images of this plant on the Taylor Beach/Gooch Creek page .  Fast forward twenty years or so until 2009. I received a call from the Invasive Plant EDRR Coordinator | B.C. Ministry of Forests, Lands & Natural Resource Operations

Fast forward twenty years or so until 2009. I received a call from the Invasive Plant EDRR Coordinator | B.C. Ministry of Forests, Lands & Natural Resource Operations

PO Box 9513, 8-727 Fisgard St, Victoria B.C. CANADA V8W 9C1. She indicated that there were 9 populations of the introduced species Phragmites australis (Cav.) Trin. in BC and it was their mandate to control all of them. She came out to the farm, took samples and pictures and I sent her pictures of the extent of the grass in the marsh over the last few years indicating it really hadn’t spread that much. She made reference to a sample in the RBC museum which had been collected from our pond in 1992 which was identified as the introduced variety.

She indicated she would be out with a crew in the fall to cut the plants to the ground and spray with the herbicide Glyphosate . (and this being next to a sea-run cutthroat stream!)

On their website, the locations of this plant in BC were identified . When the call came that they were coming out, I started to do research on the species. I valued this plant as a great nesting habitat for red-winged blackbirds, and in the summer they get infested with aphids, providing food to wasps, marsh wrens and other birds. In addition, the hollow stems made excellent homes for Mason Bees.

The red stems mentioned on the Oregon ID website are visible in the growing season on our population of reeds. I checked in early Dec.2013 and the red color is still visible.

I referred to a website from the Government of Oregon, which gave a comparison on the physical features of native , (Phragmites australis subsp.americanus) and introduced species samples. It looked very much like the native species to me, with most of the morphological characteristics corresponding. It also indicated that DNA analysis of tissue samples was the only definitive way to determine the genotype of the species.

I also contacted Dr. Adolf Ceska for his opinion, he indicated that the invasive variety probably came into BC in the 1980s. This population in our marsh was well established before the 1980s, and has not progressed very much since then. It is in a seasonal estuary, it floods with fresh

This species reproduces both asexually by underground root-stalks as well as sexually by seeds born on panicles such as this.

water with heavy winter rains, but only gets flooded with a salt water intrusion at high tides driven by a east-wind driven storm surge. (winter only)

I tend to think that the salt water controls its distribution somewhat in this particular marsh. Interestingly, in recent years cattails have spread in the pond and they were previously also controlled by salt water. The main invasive in the marsh is reed canary grass.

I tend to think that the salt water controls its distribution somewhat in this particular marsh. Interestingly, in recent years cattails have spread in the pond and they were previously also controlled by salt water. The main invasive in the marsh is reed canary grass.

I told the Invasive Plant EDRR Coordinator when she showed up with her crew of two to “remove it” that I would not allow it unless it was proven to be the invasive by DNA analysis. I heard back from her in the spring 2014.

Phragmites australis subsp. americanus growing in the Gooch Creek marsh (in November) of the year

In December of 2013, I was contacted by a wetlands restoration company from Nanaimo, BC about the population, as they found out from the RBC museum that our population was the native variety. I had not heard this yet so I contacted Dr. Ken Marr at the museum, and he indicated that DNA tests had been done and that it was indeed the native species.

- He writes “At this very moment I happen to be at UVIC looking at the raw data from the DNA analysis that was mostly completed a year ago. We have been doing a parallel study of morphology and DNA of 140 or so samples of Phragmites. Long story short, we have determined from the DNA analysis, that the populations on your land are the native genotype. In fact, the analysis of the the sample from your land convinced the coordinator of the value of doing the DNA analysis since she had thought the plants on your land were the invasive genotype. Her conclusion may have been based upon my tentative ID of a specimen collected in 1992(?) from your land and that I thought to be the invasive genotype using the characters that have been used to distinguish the native from the invasive. All who have worked on this group acknowledge that for some individual plants, it is difficult to be certain which genotype to which a plant belongs, however DNA markers are viewed to be unambiguous.”

So having regained its “native species” reputation it is protected. The moral of the story is that we must not act impulsively on eliminating introduced species unless we are absolutely certain of the species, and in the case of Phragmites, DNA testing is a minimum requirement before extirpation is promoted.

- One value added aspect of the dead hollow stems of Phragmites australis subsp. americanus is that they make great Mason Bee homes. The bottom metre and a half of the larger stems have internode lengths of up to 20 cm, and the inside diameter of the stems is 8 mm.

-

4. Swearingen, J. and K. Saltonstall. 2010.

Phragmites Field Guide Distinguishing Native and Exotic Forms of Common Reed (

Phragmites australis) in the United States. Plant Conservation Alliance, Weeds Gone Wild.

5. from The Encyclopedia of Earth,

Phragmites australis – cryptic invasion of the Common Reed in North America, “Kristin Saltonstall of the Smithsonian Tropical Research Institute has conducted a series of groundbreaking genetic analyses on P. australis. Her research has identified 29 unique genetic types, or haplotypes, of the grass globally. Of these, 13 are native to North America and historical pre-1910 samples indicate a wide distribution of these native haplotypes across the continent. Modern sampling has revealed the widespread presence of a non-native haplotype growing throughout North America. This newcomer’s DNA matches that of a Eurasian haplotype that is the most common P. australis haplotype in the world.”

Kingdom Plantae – plantes, Planta, Vegetal, plants

Subkingdom Viridaeplantae – green plants

Infrakingdom Streptophyta – land plants

Division Tracheophyta – vascular plants, tracheophytes

Subdivision Spermatophytina – spermatophytes, seed plants, phanérogames

Infradivision Angiospermae – flowering plants, angiosperms, plantas com flor, angiosperma, plantes à fleurs, angiospermes, plantes à fruits

Class Magnoliopsida

Superorder Lilianae – monocots, monocotyledons, monocotylédones

Order Poales

Family Poaceae – grasses, graminées

Genus Phragmites Adans. – reed

Ed. Note: Species subspecies americanus is the native species

in North America. Phragmites australis (Cav.) Trin. ex Steud. – common reed

-introduced species in North America

See posts on the use of Phragmites stems for culturing Mason Bees here:http://www.gfletcher.ca/?tag=phragmites